Tuesday, 23 September 2008

Wednesday, 10 September 2008

Cincin Tertutup dan Sistem Sertifikasi

Fahrul P. Amama

Indonesia telah lama dikenal dengan kekayaan keanekaragaman hayatinya. Di antara kekayaan keragaman satwanya, burung merupakan salah satu kekayaan hayati yang paling menakjubkan. Indonesia memiliki sekitar 1593 jenis burung yang menempatkan Indonesia sebagai nomor empat terbanyak di dunia. Lebih menakjubkan lagi, 353 jenis di antaranya merupakan jenis unik dan endemik (hanya terdapat di Indonesia), yang membuat Indonesia melesat ke posisi nomor satu di dunia dalam hal keanekaragaman jenis burung endemik.

Namun sayangnya, keanekaragaman jenis burung yang kita miliki semakin terancam keberadaannya. Saat ini terdapat 119 jenis burung yang terancam punah sehingga menempatkan Indonesia sebagai negara yang burungnya paling banyak terancam punah. Sementara sekitar 195 jenis burung lainnya tengah antre sebagai jenis burung yang mendekati terancam punah. Kondisi ini tidaklah makin membaik dari waktu ke waktu. Pada tahun 1994 di Sumatera tercatat sebanyak 26 jenis burung terancam punah. Jumlah ini meningkat pada tahun 2001 menjadi 195 jenis.

Ada beberapa penyebab terancam punahnya berbagai jenis burung di Indonesia. Antara lain adalah hilangnya habitat, terutama habitat hutan, yang menjadi tempat hidup burung. Luas hutan yang hilang di Sumatera dalam kurun waktu 1985-1997 mencapai angka 67.000 km2, sementara Kalimantan lebih parah lagi karena telah kehilangan 90.000 km2 kawasan hutannya. Dari 16 juta hektar luas hutan yang dimiliki Sumatera pada tahun 1900, kini tinggal tersisa hanya sekitar 300.000 hektar.

Ancaman lainnya adalah penangkapan, perdagangan serta penyelundupan burung-burung terutama jenis-jenis eksotis seperti paruh bengkok. Di kawasan timur Indonesia, ribuan ekor nuri dan kakatua ditangkap setiap tahunnya untuk diperdagangkan. Sebagian besar diselundupkan ke luar negeri, sebagian lainnya dipasok untuk memenuhi permintaan pasar domestik.

Dampak Hobi Memeliharaa Burung di Perkotaan

Hobi memelihara burung yang berkembang di Indonesia juga memberi dampak yang cukup signifikan terhadap kelestarian jenis burung. Hasil survey yang telah dilakukan oleh Burung Indonesia bersama Universitas Oxford dan Darwin Initiative, bekerja sama dengan The Nielsen menunjukkan,1,486,000 burung tangkapan dari alam dipelihara di enam kota besar di Jawa dan Bali. Survey yang sama juga memperlihatkan bahwa dari total jumlah burung kicauan yang dipelihara, lebih dari setengah (58%) merupakan jenis hasil tangkapan dari alam. Sementara sepertiga diantaranya (32%) merupakan jenis domestik. Hanya sekitar 8% yang merupakan jenis yang sebagian telah ditangkarkan, dan cuma 2% yang merupakan jenis yang sekarang banyak ditangkarkan. Berdasarkan hasil analisis di empat kota besar di Jawa, ditemukan pula bahwa terjadi peningkatan jumlah burung kicauan lokal yang dipelihara dari hasil tangkapan di alam. Pada tahun 1999 jumlahnya mencapai 738.518 ekor sementara pada tahun di tahun 2006 jumlahnya meningkat menjadi 878.077 ekor.

Untuk beberapa jenis burung, penangkapan di alam bisa menyebabkan jenis ini semakin sulit ditemui. Banyak jenis burung yang dahulunya sangat umum dijumpai menjadi semakin kecil populasinya di alam sehingga semakin langka karena banyak ditangkap dan diperdagangkan. Sebut saja sebagai contoh: cucak rawa, murai batu, jalak suren dan anis kembang. Lebih celaka lagi, jenis-jenis yang banyak diburu untuk dijadikan klanengan dan pelomba itu bukan termasuk jenis burung yang dilindungi. Kalaupun jenis tersebut kemudian dilindungi, upaya penegakkan hukum juga belum tentu efektif. Sementara populasi di alam tetap semakin rentan, sehingga diperlukan upaya pemulihan populasi tersebut.

Pendekatan Baru Untuk Pelestarian Burung

Burung Indonesia sebagai lembaga konservasi memiliki misi utama menjaga keragaman burung Indonesia dan habitatnya, serta bekerjasama dengan masyarakat untuk mencapai pembangunan yang lestari. Disadari bahwa selama ini upaya-upaya yang dilakukan untuk menjaga kelestarian jenis-jenis burung di Indonesia masih belum efektif. Karena itu perlu dikembangkan pendekatan-pendekatan baru dalam upaya pelestarian jenis burung sehingga tujuan melestarian keragaman burung di Indonesia dapat dicapai melalui cara-cara yang efektif.

Selama ini pendekatan yang lebih banyak digunakan untuk melestarikan keragaman jenis burung adalah pendekatan regulasi. Strategi utama pendekatan ini adalah menghentikan atau membatasi pasokan burung/satwa dari alam melalui peraturan eksternal dan penegakan hukum. Pendekatan ini seperti memutus rantai pasar dari produsen/pemasok kepada konsumen/pembeli. Pendekatan regulasi banyak digunakan untuk menghentikan perdagangan daging satwa liar dari alam, perdagangan harimau, maupun perburuan gading gajah untuk dijual. Komponen utama dari pendekatan ini tentunya penegakkan hukum yang efektif, tidak pandang bulu, serta memberikan efek jera bagi pelaku. Sayangnya penegakkan hukum untuk kejahatan hidupan liar (wildlife crime), seperti juga bagi kejahatan di bidang lainnya, hingga saat ini masih sangat lemah.

Pertanyaan yang kemudian muncul adalah, apakah pendekatan regulasi ini cocok dan tepat untuk diterapkan begi semua jenis burung, terutama burung kicauan? Untuk menjawab pertanyaan ini, Burung Indonesia bekerjasama dengan the Nielsen, PBI dan Aksenta melakukan studi cukup mendalam mengenai aspek hobi memelihara burung kicauan yang berkembang di Indonesia. Studi ini mencakup survey kuesioner di enam kota besar di Jawa dan Bali, analisis rantai pasar dari perdagangan burung liar dari pasokan alam di Sumatera dan Kalimantan, serta studi mengenai penangkaran burung kicauan yang berkembang di beberapa kota di pulau Jawa.

Hasil Survey Kuesioner di Enam Kota Besar di Jawa dan Bali

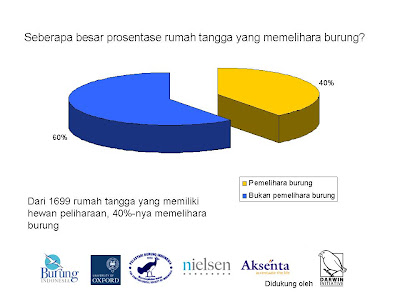

Burung Indonesia bersama Universitas Oxford, Darwin Initiative, dan Nielsen pada akhir tahun 2006 melakukan serangkaian penelitian mengenai hobi memelihara burung dalam sangkar (bird keeping) yang sangat jamak di negeri ini. Survei dilakukan di enam kota besar yang dinilai representatif yakni Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Semarang, Surabaya, dan Denpasar. Hasilnya, burung adalah satwa yang paling banyak dipelihara keluarga Indonesia. Dari 1.781 rumah tangga di kota-kota besar itu, sebanyak 636 atau sekitar 36 persen rumah tangga memilih burung sebagai binatang peliharaan. Artinya, bisa diasumsikan kalau 1.486.611 rumah tangga di enam kota besar seantero Jawa-Bali yang memelihara burung.

Ini adalah angka terbesar dibanding data hewan peliharaan lain. Ikan hanya dipelihara oleh 434 rumah tangga atau sekitar 24 persen, kucing hanya dipelihara 228 orang (13 persen), dan anjing dipelihara 179 rumah tangga atau sekitar 10 persen. Sisanya dengan persentase yang relatif kecil sekitar satu sampai lima persen adalah reptil, monyet, dan binatang-binatang yang dipandang langka dan unik lainnya.

Fakta ini tidak lepas dari budaya memelihara burung yang telah mengakar kuat dalam sanubari masyarakat, terutama kalangan masyarakat Jawa. Budaya Jawa yang mendasarkan kekuatan jiwa pada lima hal – yang salah satunya adalah burung – itulah yang melatarbelakangi banyak orang Jawa memelihara burung. Dari survey juga terungkap, alasan utama banyak orang memelihara burung adalah burung mengingatkan pemeliharanya akan suasana asri di kampungnya. Burung juga menjadi sarana yang baik dalam memperluas dan mempererat pertemanan di kalangan masyarakat penghobi. Di samping itu, hobi memelihara burung juga meningkatkan minat serta pengetahuan mereka mengenai berbagai aspek pada burung kicauan.

Kalangan penghobi burung juga merasakan berbagai manfaat dalam menekuni hobi mereka. Salah satunya adalah melepaskan stress dan membuat suasana lebih santai di rumah. Selain sebagai kegiatan pengisi waktu luang, burung juga merupakan bahan pembicaraan yang menyenangkan bagi kalangan penghobi dalam mempererat persahabatan dan kekeluargaan.

Dari segi ekonomi, hobi memelihara burung juga memberikan dampak yang sangat signifikan bagi masyarakat. Rata-rata penghobi mengeluarkan uang sekitar 1,5 juta rupiah setiap tahunnya untuk burung kicauan. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa perputaran uang dalam hobi burung kicauan per tahunnya mencapai 800 Milyar rupiah. Tak hanya dari segi besaran rupiahnya, perputaran uang dalam hobi burung kicauan juga memberikan multipyer efek yang sangat signifikan bagi masyarakat luas. Perputaran uang dalam satu even lomba saja dapat mencapai 500 juta rupiah. Fakta di lapangan menunjukkan bahwa keberadaan lomba tersebut membuka peluang usaha bagi sektor informal seperti pedagang kaki lima, perajin sangkar, penjual pakan hidup dan usaha lainnya. Dalam sektor penangkaran burung sebagai salah satu pemasok burung kicauan, juga terlihat banyak peluang bagi masyarakat untuk meningkatkan pendapatannya sebagai penangkar, pengumpul pakan hidup, hingga perawat anakan yang bertugas melolohkan makanan. Sektor ini juga membuka peluang bagi masyarakat di desa untuk tetap memperoleh pendapatan yang signifikan pada usia yang dianggap sudah non produktif.

Pendekatan Pasar dan Sistem Sertifikasi

Kesimpulan yang dapat diambil dari studi tersebut adalah hobi memelihara burung kicauan memberikan keuntungan sosial, budaya dan ekonomi yang signifikan. Namun di sisi lain, hobi memelihara burung juga memberikan dampak pada populasi burung liar jika pasokan burung hanya diambil dari alam. Untuk itu diperlukan pendekatan yang berbeda dalam upaya pelestarian burung, yakni pendekatan pasar.

Pendekatan pasar bertujuan memodifikasi rantai pasokan dengan kontrol pasar (market ‘pulls’ & pushes). Pendekatan ini lebih menitikberatkan kepada kesadaran para pelaku pasar serta karisma. Dengan pendekatan ini, rantai pasar tidak diputus seperti yang dilakukan pada pendekatan regulasi. Modifikasi rantai pasokan dilakukan untuk menjamin keberlangsungan rantai pasar itu sendiri. Modifikasi ini dilakukan dengan merubah pasokan langsung dari alam dengan tiga komponen.

Komponen pertama adalah bahan pengganti. Contoh nyata dari komponen ini adalah kayu hitam (ebony) dan gading gajah (ivory) yang menjadi bahan utama pembuatan piano. Dengan digantikannya bahan tersebut dengan plastik, otomatis mengurangi permintaan terhadap gading gajah dan kayu hitam dari alam.

Komponen kedua adalah pemanfaatan berkelanjutan. Komponen ini tidak menghentikan pasokan dari alam, tetapi proses pemanenan dari alam dibatasi serta dikontrol sehingga tidak mengancam keberlanjutan jenis yang dipanen. Pembatasan dapat berupa masa pemanenan, jumlah kuota pemanenan serta spesifikasi jenis yang boleh dipanen (ukuran, usia dan lainnya).

Komponen lainnya adalah pembiakan/penanaman, yang untuk dunia satwa dikenal dengan penangkaran. Komponen ini sangat penting untuk perlahan-lahan menggantikan ketergantungan terhadap pasokan langsung dari alam. Sehingga pengambilan langsung dari alam nantinya dapat sangat dibatasi, misalnya hanya untuk dijadikan indukan bagi penangkaran.

Ketiga komponen tersebut juga dikontrol dalam rantai pasar dengan menggunakan sertifikasi. Dengan demikian dampak negatif terhadap populasi di alam dapat dikurangi tanpa memutus rantai pasar. Dalam pendekatan ini sertifikasi menjadi komponen penting dalam memodifikasi rantai pasar sehingga dapat menjamin keberlanjutan.

Berbagai kalangan penghobi burung kicauan kini sedang mendiskusikan kemungkinan untuk mengganti penangkapan di alam dengan budidaya/penangkaran. Untuk itu perlu dilakukan penandaan sehingga dapat dibedakan burung hasil tangkaran dengan burung hasil tangkapan alam. Untuk menjamin keabsahan penandaan tersebut dibutuhkan sistem sertifikasi bagi burung hasil tangkaran. Salah satu kemungkinan adalah membentuk suatu sistem dimana anakan burung hasil budidaya akan ditandai dengan cincin khusus yang akan membuktikan bahwa burung tersebut adalah hasil dari penangkaran. Cincin khusus ini disebut cincin tertutup (close ring) yang sifatnya permanen. Ukuran cincin tersebut disesuaikan sedemikian rupa berdasarkan ukuran kaki jenis burung tertentu sehingga hanya dapat dipasang di kaki burung pada saat masih anakan.

Tujuannya sertifikasi dan pencincinan ini adalah supaya orang dapat membedakan antara burung hasil penangkaran dengan hasil penangkapan di alam. Dengan demikian konsumen dapat memilih untuk membeli burung hasil tangkaran jika diinginkan. Diharapkan dengan adanya sertifikasi dan pencincinan ini para penghobi burung kicauan dapat mengambil bagian dalam upaya mengurangi pengaruh hobi memelihara burung terhadap populasi burung di alam.

Fahrul P. Amama bekerja di Knowledge Center Burung Indonesia sebagai Social Marketing and Campaign Officer.

Bird-keeping in Indonesia: conservation impacts and the potential for substitution-based conservation responses

Paul Jepson and Richard J. Ladle

Oryx Vol 39 No 4 October 2005

Abstract

Bird-keeping is an extremely popular pastime in

Keywords Birds, bird trade, CITES, culture,

Introduction

The international conservation movement is unified in the belief that human use and trade of wildlife should not endanger wild populations. This principle found widespread support among governments of the community of nations and is the basis of the 1973 Convention on Trade in Endangered Species (CITES Secretariat, 2000). This convention promotes legal and regulatory mechanisms as the means to put this principle into practice. A central feature of the treaty is three lists of species at risk from trade (Appendices I–III), which establish increasingly stringent international trade restrictions on the species concerned. In many less-developed countries assuring CITES compliance is the primary driver of national level policy meetings on wildlife trade. Consequently CITES regulatory discourse tends to dominate the thinking of local policy makers and frame how they conceptualize responses to both international and domestic wildlife trade (Reeve, 2002). To avoid perpetuating the misconception that trade (regulatory) measures alone constitute an effective policy response when a species is threatened by trade (Dickson, 2003), we suggest that more debate is needed on the efficacy of market-led approaches in less-developed countries.

Two such market-led approaches gaining widespread acceptance are sustainable offtake and substitution, either with cultivated or farmed wild species or alternative products. These measures have been applied to major extraction industries such as forestry (timber, non-timber forest products; Shanley et al., 2002), fisheries (MSC, 2002), ‘collectables’, notably orchids (Orlean, 2000), medicinal plants (Schippman et al., 2002) and the aquarium-fish sector (Wabnitz et al., 2003). They incorporate the recognition that for some commodity chains it is impractical and/or undesirable on social, cultural and economic grounds to ban trade and consumption of natural products. In addition they reflect the rise of ‘sustainability’ in international policy discourse (Princen & Finger, 1994) and the idea of ethical or ‘green’ consumerism that posits that supply chains can be changed by empowering consumers to make informed and ethical decisions over which products or brands they purchase.

Capture for the pet trade is the primary threat category for 34 bird species in Asia and is a major problem for several threatened birds in

Fig. 1 Map of

Here we consider three questions. Firstly, is birdkeeping in

Methods

The present survey was piggy-backed on the March 1999 biannual OmnibusTM household survey conducted by the consumer survey company A.C. Nielsen. This survey samples a population of 1,740 randomly selected households in

For the purpose of analysis, data was consolidated into five conservation impact categories: (1) domestic species, (2) commercially-bred native species, (3) wildcaught native songbirds, (4) wild-caught native parrots, (5) wild-caught imported songbirds (Appendix 1). Birds kept in categories 1 and 2 are of limited conservation concern, whereas keeping birds in categories 3–5 may result in negative conservation impacts. Allocation of respondent answers to each of these categories was reviewed by an independent expert on Indonesian birdkeeping and bird names (S. van Balen). In this survey chicken was treated as a category of pet different to a bird, in accordance with the folk taxonomy followed by many Indonesians who lack a biological training.

We generated an estimate of the total number of birds kept in each category by multiplying the number of households keeping a bird by the average number of birds kept. To generate an estimate of the number of birds acquired per year we first converted the response categories on length of time a bird was kept to an acquisition rate (i.e. a check in the 1–3 month category equates to 1 bird acquired per 3-month period, a check in the 3–6 month category equates to 0.5 birds acquired in a 3-month period, and so on), and then multiplied the mean acquisition rate for a category by the estimated number of birds kept.

Results

This survey found that birds are the most popular household pet in the sample population. In the five major cities, 21.8% (380/1,740) of households surveyed kept a bird, compared with 16.6% (289/1,740) keeping a chicken, 9.5% (165/1,740) a fish, 3.4% (9/1,740) a cat, and 2.7% (47/1,740) a dog. The frequency of bird ownership extrapolates to an indicative total of 1,261,600 households keeping a bird. The indicative number of birds kept in five conservation categories is 2,823,740 and the estimated number of birds acquired per year is 2,457,760.

The incidence of keeping of hill myna and straw-headed bulbul, which were species of particular conservation interest at the time of the survey, was low (n=8 and 15, respectively). Domestic and commercially-bred species account for 65.8% of the total (Table 1).

There were significant differences in the proportion of the sample population keeping birds in different cities (x2=69.358, n=1,360, df=4, P<0.001). In

Respondents named 38 species or species groups as being kept in addition to the five predefined response categories (Appendix 1). Species in the two categories of least conservation concern were owned by 78.4% (298/380) of households keeping birds, whereas 60.2% (229/380) kept a species in the three categories of conservation concern (i.e. wild-caught). Native song-birds were by far the most popular category kept (86.8%, 330/380 of households keeping a bird) and the proportion classed as commercially-bred slightly exceeds that classed as wild-caught (44.5% vs 42.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1 Indicative number of birds kept and acquired in

Fig. 2 Mean numbers (PSE) of birds kept by households in

Non-parametric bivariate analysis revealed consistent patterns in respondents’ socio-economic status, education, age group and bird ownership. Overall, households keeping birds had a higher household income and educational attainment but age group was not significantly different. Specifically, households owning a bird in the three conservation concern categories were richer and better educated, whereas households owning commercial-bred species were richer but not better educated, and households keeping domestic species did not differ from households not keeping birds (Table 2).

In the sample surveyed 56.1% (193/380) of respondents said they obtained their birds from a bird market or door-to-door seller (who work on behalf of market traders), 46.8% (178/380) from a friend or relative and 10% (38/380) said they caught their birds. We found no significant difference in the relative proportions of respondents obtaining their birds in these ways between the cities. However, analysis of the socio-economic attributes revealed that richer and more educated households buy from markets or door-to-door sellers, whereas poorer, less-well educated households are more likely to catch their birds. There were no significant differences between socio-economic attributes of households that did or did not obtain their bird as a gift or from a friend (Table 2).

Table 2 Results of bivariate analysis (Mann Whitney U tests) of socio-economic status (SES), educational background category and age group for the five conservation impact categories (see text for details).

Discussion

This survey constitutes the first empirical profile of the bird-keeping hobby in

The survey findings confirm the cultural significance of bird-keeping in

Our finding that bird-keeping is most popular in

However, it is also important to note that

because the latter could be perceived as an attack on or interference with their cultural identities.

Our findings suggest that c. 2.5 million birds are acquired by households each year, of which 758,250 are wild-caught native songbirds, 60,230 are wild-caught native parrots, and 146,210 are wild-caught imported songbirds. Considering that the five cities sampled represent only a quarter of Indonesia’s 80 million urban population and bird-keeping is also popular in rural areas, our figures suggest that Nash’s (1994) estimate of 1.3 million wild-caught birds per year may be conservative. However, we stress that our figures relate to birds acquired by a household and not from the wild. Long-lived species such as parrots may change hands several times before they die and in this category the number of birds taken from the wild may be substantially less than our indicative figure of 50,590 acquired per year. Conversely, mortality of wild-caught songbirds in the supply chain between the point of capture and purchase by a bird hobbyist is believed to be high and the indicative figure of c. 614,000 may be an underestimate of the birds taken from the wild.

Our survey lacks the precision to estimate the numbers of threatened or CITES-listed species involved. The list of species named by respondents suggests that bulbuls Pyconotus spp., starlings Sturnus spp. and whiterumped shama Copsychus malabaricus were among the more popular wild-caught native species kept. In the absence of data on populations of commoner species in

The large number of domestic and commercially-bred species kept show that substitution is already happening on a large scale. This is borne out by the fact that bird-farms (mostly located in East Java) were the fifth ranking buyer of magazine advertising space in 1999 (A.C. Nielsen, own data). Moreover, the large proportion of birds acquired as a gift or from a friend or relative suggests that small-scale breeding and exchanging of birds among hobbyists is widespread.

A key finding of this survey is that bird-keeping is commoner among richer households and that wildcaught species are kept more frequently in richer and better educated households. These households are easiest to reach and more likely to be swayed by social marketing techniques promoting commercially-bred alternatives. This is because hobbyists in these households are likely to buy specialist magazines, be members of clubs and societies, and more able and willing to make an ethical choice.

In summary, this study finds that bird-keeping among urban Indonesians is of a scale that warrants a conservation intervention and exhibits a profile that suggests substitution with commercially-bred alternatives would be an effective response. Two additional points merit note.

Firstly, whilst the cost of some wild-caught species is low that of several species of conservation concern is high. For example, at the time of this study straw-headed bulbuls were selling for USD 120, hill mynas for USD 85–250 depending on their vocal repertoire, and Zoothera thrushes for >USD 200 (Jepson et al., 1998; P. Jepson, unpubl. data; C. Trainor & I. Setiwan, pers. comm.). Whilst the breeding of many ‘soft-bill’ species is difficult, the value of some species and the size of the market may be sufficient to interest investors willing to overcome the technical challenges that commercial breeding of these species may pose.

Secondly, the bird-keeping hobby revolves around a sophisticated appreciation of bird song, form and coloration. Birds with a pedigree of winning song contests or with a novel vocal or physical characteristic are particularly sought after. For example, in 1998 hill mynas able to sing Ricky Martin’s World Cup theme song appeared on the market and fetched three or four times the normal price. Commercial breeding can produce birds with pedigree or vocabularies and endearing behaviours. Marketing such birds as a superior ‘product’ to a wild-caught bird would generate business as well as conservation benefits.

This survey did not provide sufficient data to design and develop a market-led response to mitigate impacts of the bird-keeping hobby on wild bird populations. Although our survey technique enabled a large population to be surveyed at low cost it lacked precision and deep insight. A dedicated survey adopting social marketing principles would be needed to design a campaign aimed at changing the culture of bird-keeping in Java. We suggest that this should include an attitude survey of hobbyists to ascertain their motivations and preferences, and to generate the knowledge base for a targeted social marketing campaign. This should be coupled with exploratory meetings with bird farms to ascertain the

feasibility of breeding species of conservation concern, their interest in doing so, and their readiness to engage with some sort of accreditation and labelling scheme that would provide assurance that wild-caught birds cannot enter the supply chain.

References

BirdLife International (2001) Threatened Bird of

BirdLife International (2003) Saving

CITES Secretariat (2000) Strategic Vision through 2005. CITES Secretariat,

Dickson, B. (2003) What is the goal of regulating wildlife trade? Is regulation a good way to achieve this goal? In The Trade in Wildlife. Regulation for Conservation (ed. S. Oldfield), pp. 23–32. Earthscan,

Holmes, D. (1995) Editorial. Kukila, 7, 85–90.

Jepson, P., Momberg, F. & van Noord, H. (1998) Trade in the Hill Myna Gracula Religiosa from the Mahakam Lakes Region, East Kalimantan. PHPA/WWF-Indonesia/EPIQ/USAID Technical Memorandum,

MSC (2002) The Marine Stewardship Council. Http://www.msc.org [accessed 29 June 2005].

Nash, S.V. (1994) Sold for a Song. The Trade in Southeast Asian Non-CITES Birds. TRAFFIC International,

Oey, E. (1997) Java. Periplus Editions,

Orlean, S. (2000) The Orchid Thief. Vantage,

Princen, T. & Finger, M. (1994) Environmental NGOs in World Politics. Routledge,

Reeve, R. (2002) Policing International Trade in Endangered Species. The CITES Treaty and Compliance. Earthscan,

Schippman, U., Leaman, D.J. & Cunningham, A.B. (2002) Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues. Interdepartmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture, FAO,

Shanley, P., Pierce, A.R.,

Wabnitz, C.,

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Farquhar Stirling, Head of A.C. Nielsen

Biographical sketches

Paul Jepson was formerly head of the BirdLife International-Indonesia Programme (1991–1997), which included a significant field and policy component on bird trade. His research interests include conservation governance, protected area policy and wildlife trade. He is leading a new project to assess the efficacy of market-led mechanisms to mitigate the conservation impacts of bird-keeping in Java, funded by the Darwin Initiative.

Richard Ladle is the Director of Oxford University’s MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management. His research interests include the representation of conservation in the media, assessment of public attitudes to conservation and the environment, conservation biogeography, and the application of market-led solutions to environmental and conservation problems.

Paul Jepson (Corresponding author) and Richard J. Ladle Biodiversity Research Group & Environmental Change Institute, Oxford University Centre for the Environment, Dyson Perrins Building, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UK. E-mail paul.jepson@ouce.ox.ac.uk

Received 2 August 2004. Revision requested 10 November 2004. Accepted 7 February 2005.

© 2005 FFI, Oryx, 39(4), 1–6 doi:10.1017/S0030605305001110 Printed in the

Friday, 29 August 2008

Thursday, 28 August 2008

Monday, 14 July 2008

A bird in a cage puts all Java in a craze

By Paul Jepson

When was the last time you really listened to a bird sing? For many British bird-watchers bird song is simply a tool to identification and it is perhaps only whilst relaxing in the garden or during a dawn chorus event that most of us stop to really listen. In the cities of Java the massive popularity of birds revolves arounds their song, and the beautiful song of one particular thrush arouses such passion amongst bird enthusiasts that the best singers exchange hands for upwards of £15,000.

An appreciation of birds is deeply rooted in Indonesian culture but if you live in a city on the densely populated tropical island of Java our mode of bird-watching is not really an option: there are no accessible reserves, green space is rare, the traffic jams are awful, it's sweltering hot, pours with rain most afternoons, and what birds there are suffer heavy persecution. Given these conditions is hardly surprising that Indonesians love their cage-birds. A recent survey found that one-in-five urban households keep a bird and when asked why, most respondents chose the answer ‘to remind me of my village’. Amongst urban bird keepers the pride and satisfaction that villagers traditionally take from rearing animals is finding a new and cosmopolitan expression in the form of songbird contests.

Songbird contests take place every weekend in city parks. These events are something of a morph between a horse race, dog show, football match and cockfight. The three national song contests attract 4000 or more participants and spectators and 800 competing birds. The vast majority of the birds are wild caught and from five local species with exceptional song repertoires: orange-headed thrush, long-tailed shrike, white-rumped shama, chestnut-headed thrush and leafbirds. At the (ex-president) ‘Gus Dur’ songcontest held in Jakarta in April there were 10 separate orange headed thrush ‘classes’ each attracting 30 to 40 bird entrants with the top ‘mega star’ class carrying an entry fee of £12 and winning prize of £1000. Not insignificant amounts when the average monthly income is £45!

Readers who have birded in

Competing songbirds is a relatively new hobby which draws its inspiration from the traditional Javanese practice of competing zebra doves. However, because song quality of zebra doves is determined by genetics, this hobby came to be dominated by champion breeders and the people who could afford their birds. In the mid-1970s a group of bird connoisseurs amongst the

And they were right. As a competitive songster the orange-headed thrush has it all. It’s a real looker that boasts a beautifully varied song and the ability to incorporate song-phrases from other species. It has ‘attitude’ and the stamina (with training) to sing non-stop for 25 to 40 minutes in close proximity with 20 or more other dominant males and as a bonus it postures when it sings. More correctly it goes into a drunken-looking stupor – wings and head drooped, swaying on the perch. Many birds are named after their distinctive singing posture -‘Satellite’, ‘Antenna’ and so forth.

These attributes of orange-headed thrush give it enormous popular appeal and make for exciting judging. In contrast to the staid zebra dove contests of old, the new songbird contests are dynamic, uncertain and uproarious. A new phrase in a song repertoire or a distinctive posture might capture the favour of the judges. This means lots to talk about and it opens the field to anyone with a talent for training birds and spotting a potential star.

There are about 60,000 songbird hobbyists in Java who identify themselves either with a bird club or as a ‘single fighter’ (they use the English words). A bird club Java-style is a network of hobbyists who compete against each other to train and test their birds and then compete as a team at city, provincial or national level song contests. Like a footballer, the value of an orange headed thrush jumps significantly as it proves itself at different levels of competition. A newly caught bird currently sells for around £25. Once it has shown it can compete at a local contest its value will be £90-100. If it then becomes a ‘prospect’ by, for example, coming in the top three at song contests in two or more provinces its value will increase to £1500, and so on upwards to the current record ‘transfer fee’ of £18,000.

At the core of bird clubs are networks of entrepreneurially-minded men who enjoy speculating on the value gains they can accrue using their ‘ear for a prospect’ and skill at training. Bird clubs usually comprises sub-groups of hobbyists ‘playing’ at different value levels relating to their financial means and attitude to risk. At the apex is a ‘big boss’ who will pay upwards of £10,000 for outstanding birds and lead the club in a collective enterprises of sourcing and scouting prospects, training winners and acquiring established champions. Success brings fame and prestige to the club and its members.

Although money is central to the hobby it would be wrong to surmise that most hobbyists are motivated solely by the promise of financial rewards. When asked about the appeal of the hobby they describe the satisfaction they feel when a bird they've trained successfully competes, the sense of fraternity that comes with participating as well as the opportunity to be ‘someone’, to be known, talked about and counselled on bird-related matters. Some hobbyists have a more mystical bent and talk about the experience of connecting with another life-form.

Many hobbyists comment on the fact that participating in song-contests brings people from all social strata and ethnicities into contact with networks of entrepreneurs that link city with village and city with city. It is telling that the songbird hobby took off during the Asian economic crisis of 1997 to 1998 when many men were made redundant and the expectation of employers providing a job for life was challenged. As well as building relationships with successful entrepreneurs, the hobby itself provides numerous small businesses opportunities, for example, in the production of cages and equipment, as a buyer and seller of ‘prospects’, as a personal songbird trainer (known as a ‘jockey’) and in bird breeding . The bird keeping sector contribute £42 million to the economy is of the six largest cities on Java and

The way of enjoying birds on Java clearly contributes important social and economic benefits to the contemporary urban culture. Unfortunately it also impacts negatively on the wild populations of the most popular species. Today over 120,000 orange-headed thrushes are kept in the six cities surveyed and all have been taken from the wild in the last six years. The editor of the weekly bird-keeping tabloid newspaper, believes there has been a process of rolling local extinctions across Java where thrushes in one forest block after another have been trapped out. Bird-trapping is a common weekend hobby for men living in the sprawling towns and villages close to forest areas. The appeal is probably akin to that of fishing: bait an area, set a trap, wait and reflect, and then enjoy the thrill of the catch. It makes for a nice camping weekend with the lads, which is all the easier to justify to the wife if it results in a few birds to sell!

Specialists in the sourcing of these thrushes have now found a new and potentially sustainable supply from

In response a network of like-minded individuals is forming to instil a stronger conservation ethos within the hobby. Their vision is to bring about a switch from wild- caught to captive bred songbirds on the hobby, to dissuade citizens with a casual interest from keeping birds and encourage those who really want one to by a canary, lovebird or zebra dove which are already bred in huge numbers. The first tasks of this network, which initially included scholars, businessmen and conservation professionals was to conduct the research on which this article is based. The network has subsequently expanded to include journalists and consultants and represents the hobbyists, breeder and conservation perspectives. A campaign to encourage bird-keepers to buy only captive-bred birds is getting underway and schemes to promote and certify bird-breeding are being developed. The changes sought will not happen over-night and the people involved are taking the long term view. The fact that an appreciation of birds is so widespread and deeply embedded in the urban culture of Java and

Dr Paul Jepson is Course Director of the MSc. in Nature, Society and Environmental Policy at the Oxford University Centre for the Environment and was Principal Invesitgator on the Darwin Initiative Project “A market-based conservation response to domestic bird-trade in Indonesia’ from which this brief originates. His research specializes in various aspects of conservation governance and he was previously head of the Birdlife International-Indonesia Programme (1991-1997)